Large Language Models (LLMs) are transforming industries, powering everything from chatbots to automated content creation. However, to make these models excel at specific tasks, optimisation is crucial. Prompt engineering and fine-tuning offer distinct approaches to tailoring LLMs.

This blog post will:

- Explain what prompt engineering and fine-tuning are, using simple, real-world analogies.

- Highlight their strengths and weaknesses.

- Walk through a concrete example from ComplyAdvantage’s pipeline.

By the end, you’ll understand when it makes sense to invest time in crafting fancy prompts versus training a model further on your own data.

What Is Prompt Engineering?

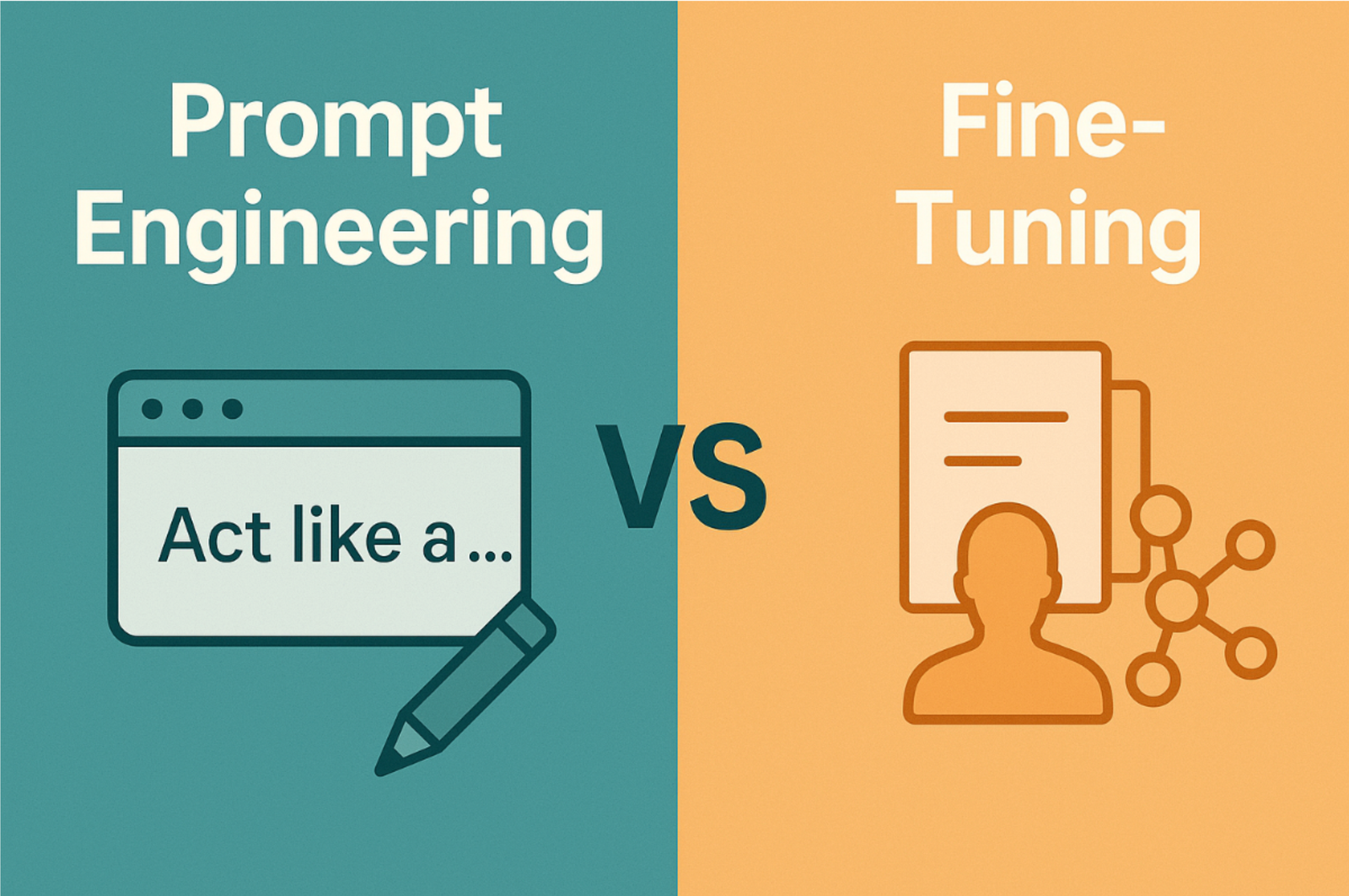

Prompt engineering involves designing the input text, or prompt, to elicit the desired output from an LLM without modifying its internal parameters.

It’s akin to phrasing a question to get the best answer from a knowledgeable friend. For instance, to classify customer support tickets, you might use a prompt like, “Classify this ticket as billing, technical issue, or product inquiry: [ticket text].” Prompt engineering relies on the model’s pre-existing knowledge, making it accessible to users without deep technical skills.

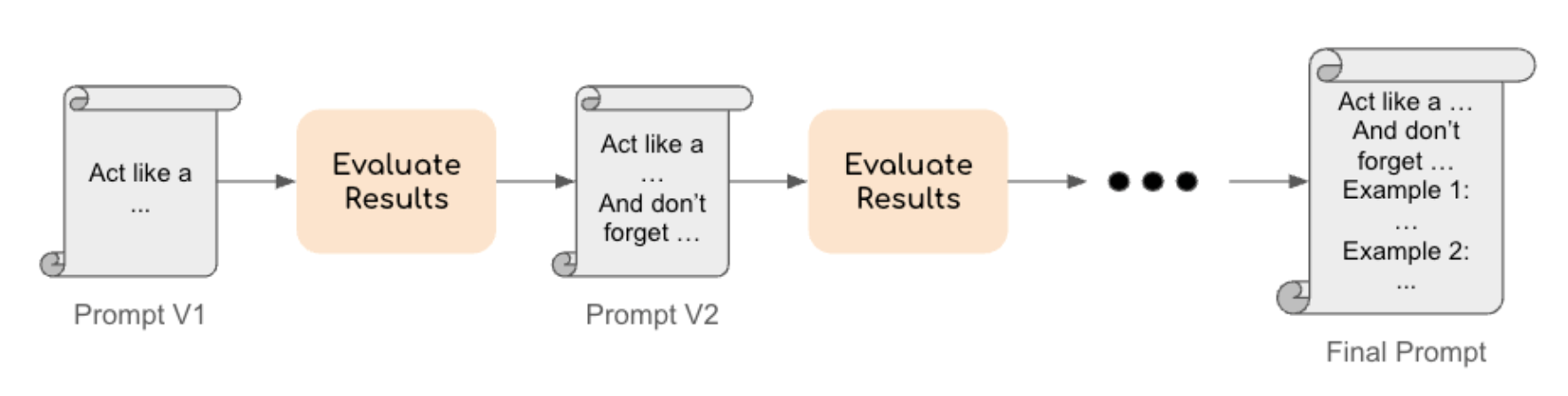

If the prompt is clear, the model usually does a good job. But if you need more complicated behaviour (like formatting, style, etc), you end up tinkering with the prompt a lot:

- Adding examples inside the prompt (few-shot prompting)

- Adding system messages (“You are an expert ticket classifier”)

- Asking for step-by-step reasoning (chain-of-thought prompting)

- Adjusting temperature or other settings

- Rewriting the text dozens of times

This trial-and-error can be time-consuming. Even then, the model might not behave perfectly on every input.

What Is Fine-Tuning?

Fine-tuning adjusts the LLM’s internal parameters by further training it on a dataset specific to the task. This process refines the model’s understanding, making it more adept at handling specialised inputs. For example, fine-tuning an LLM on a dataset of legal questions and answers can improve its ability to answer in this domain.

Think of fine-tuning like tutoring a student. You give the student homework problems (examples) and the correct solutions. Over time, the student learns exactly how to solve these problems, so whenever you give a new problem, the student knows what to do.

Since the model learns from examples, the prompt is usually much simpler. Instead, effort is put into building a representative dataset of input-output pairs that will help the LLM learn the nuances of the task at hand.

Applied Example: Labelling ComplyAdvantage data

At ComplyAdvantage, we process billions of records to identify and group real-world entities: individuals, companies, or organisations that appear in media articles, government databases, and more. One critical step in our data pipeline is Entity Resolution (ER): deciding whether two records refer to the same person or not. For instance, records like:

- “John A. Smith, born 1985, London”

- “Jonathan Smith, DOB 1985-03-12, UK”

might represent the same individual or completely different people. Deciding this requires evaluating contextual clues like name rarity, birth dates, addresses, affiliations, etc.

The Human Annotation Bottleneck

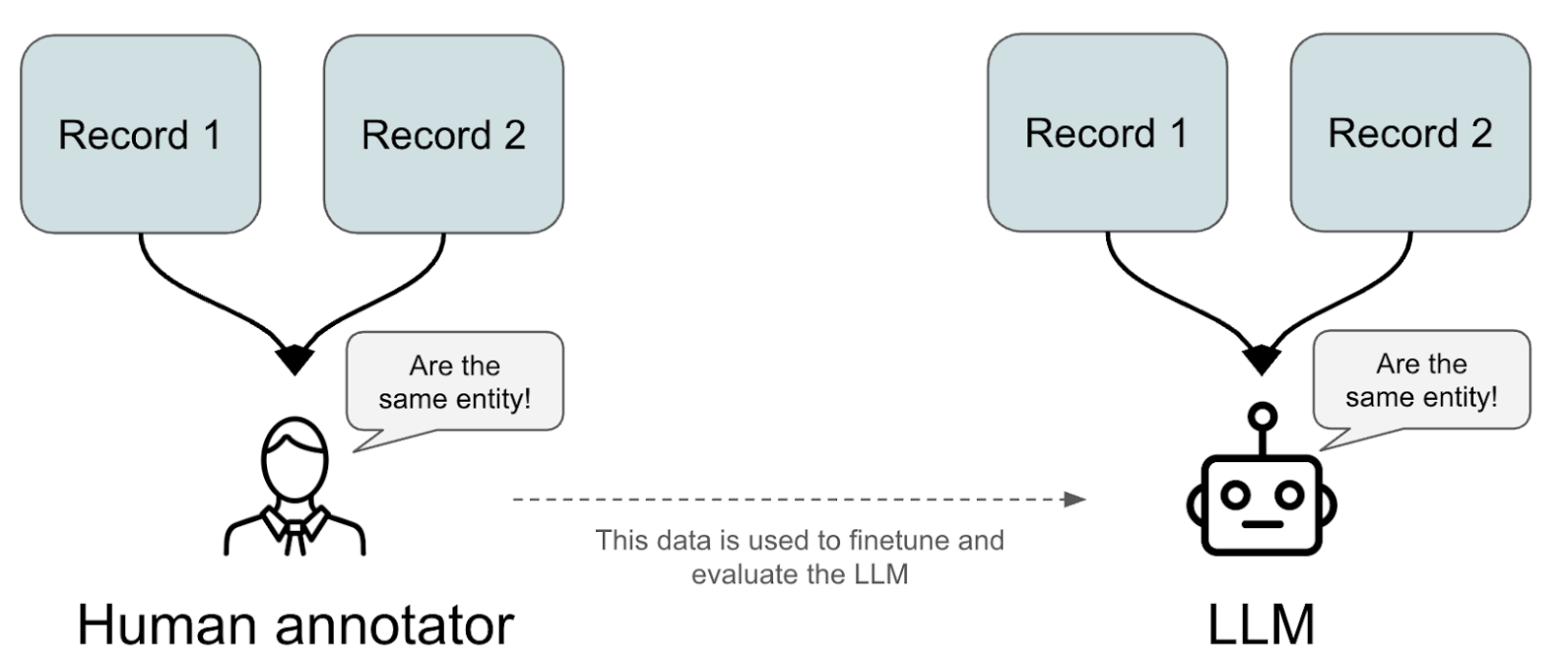

To evaluate ER algorithms, we rely on labelled datasets. Since full cluster annotations are impractical at scale, we simplify the task to pairwise comparisons: given two records, a human annotator decides if they refer to the same real-world person or not.

This manual labelling process is slow and expensive. Each decision depends on nuanced reasoning: Is the name variation acceptable? Is the missing field critical? Does this affiliation provide a strong enough link?

Attempt 1: Prompt Engineering

Our first idea was to use prompt engineering, because it’s quick to try:

- We wrote prompts like: “You are an expert in entity resolution. Given these two records, decide if they refer to the same person. Consider name variations (e.g., John vs. Jonathan), dates of birth, locations, and affiliations. Answer exactly ‘Linked’ or ‘Not Linked’ and briefly explain your reasoning.”

- We tested this on different examples. The model did great on obvious cases (e.g., identical names and birth dates). As soon as we hit borderline cases (slightly different spellings, missing fields, ambiguous affiliations), no amount of prompt tweaking solved everything. We tried:

- Adding multiple few-shot examples inside the prompt.

- Asking for step-by-step reasoning (“First check if names match, then dates…”).

- Adjusting the temperature to make the model more or less “creative.”

Despite dozens of iterations, performance plateaued at a level that still required significant human review; and this is understandable as the nuance and knowledge of how to compare similar but different information doesn’t have clear rules that can be captured in several short examples. However, in a compliance setting, that level of uncertainty was too high. We needed the system to behave reliably in the vast majority of cases - far beyond what even our most refined prompts could guarantee.

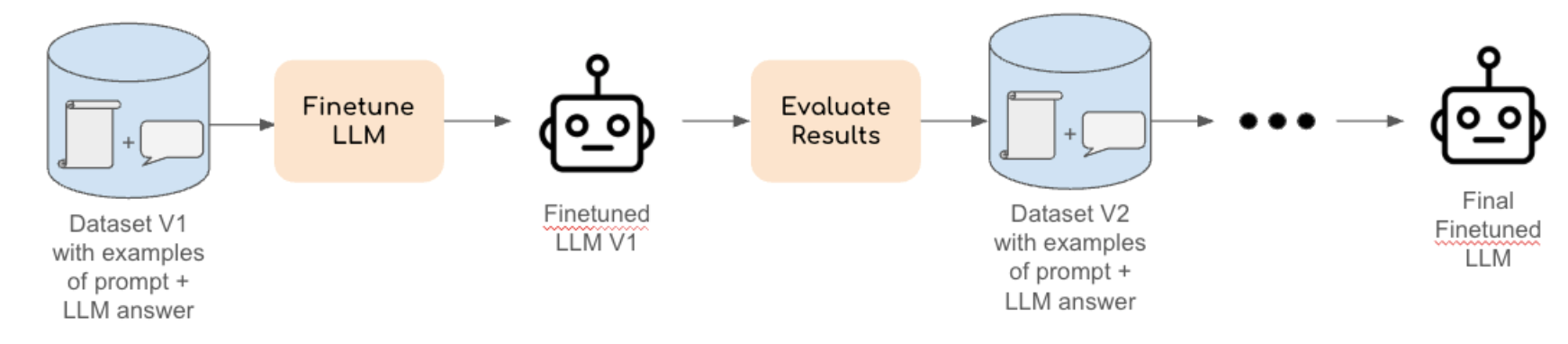

Attempt 2: Fine-tuning

Next, we gathered around 1,000 human-labelled pairs (balanced between “Linked” and “Not Linked”), carefully including common edge cases like:

- Name variations (e.g., “Alexandra Li” vs. “Aleksandra Lee”).

- Partial dates (just year vs. full YYYY-MM-DD).

- Missing fields (no nationality but matching location).

- Different data sources (news article vs sanctions list).

For each example, our dataset format looked like this (in JSONL for fine-tuning):

{

"system": "You are an expert in entity resolution. Decide if the 2 records should be ‘Linked’ or ‘Not Linked’.",

"user": "Record A:

- Name: Alexandra Li

- Born: 1985

- Location: London

Record B:

- Name: Aleksandra Lee

- Born: 1985-03-12

- Nationality: UK",

"assistant": "Linked"

}

Training Process:

- Prepare JSONL File: Combine JSONs like the one above in a single file. One example per JSON.

- Upload to the LLM API: We used the Gemini API fine-tuning endpoint.

- Monitor Training: After just half an hour of compute time, we obtained a specialised model.

Results after Fine-Tuning:

The fine-tuned model exhibited far greater consistency on both easy and edge-case examples.

The model learned to:

- Not over-penalise missing birthplace if other fields match strongly.

- Treat common nicknames (e.g., “Mike” vs. “Michael”) as equivalent when context agrees.

- Weigh conflicting features less heavily if other important features align.

- The need for complex prompts vanished - we could now simply pass the two entities to the fine-tuned model with a minimal instruction and get accurate results.

In short, showing the LLM a relatively small, well-curated dataset made it far more reliable on this specific task - compared to spending hours rewriting prompts and still missing too many edge cases.

Conclusion

Should we always fine-tune LLMs? No.

Prompt engineering and fine-tuning are two approaches to steering the behaviour of LLMs. Prompting is fast to try, works well for simple tasks, and is often preferred when the task requires more creativity and doesn’t have a concrete golden label. For instance, tasks like writing poems or creating a dinner recipe do not have a unique answer that we can teach the LLM. For these use cases, prompting usually works better since it uses the LLM’s already learned creativity, while fine-tuning might restrict it to a specific answer style.

On the other hand, if your task is highly specialised (like being an expert ER annotator) or involves constrained text generation (e.g., classification and information extraction), teaching the model with a few good examples may beat a great number of clever instructions.

However, this specialisation is a significant trade-off. While the fine-tuned model becomes an expert at its specific task, it may lose its ability to generalise, performing poorly if the task changes or a very different prompt is used. This means a fine-tuned model should be treated as a new, specialised tool and should not be used for other, unrelated tasks that the original base model could handle. Furthermore, the fine-tuning process itself can disrupt the model's original safety mechanisms. This can create new, unexpected "edge cases" or vulnerabilities that were not present in the base model. As a result, a fine-tuned model requires its own rigorous testing and evaluation to ensure it is not only accurate but also safe and reliable in its new, specialised context.