Parallelism vs Concurrency: A Quick Refresher

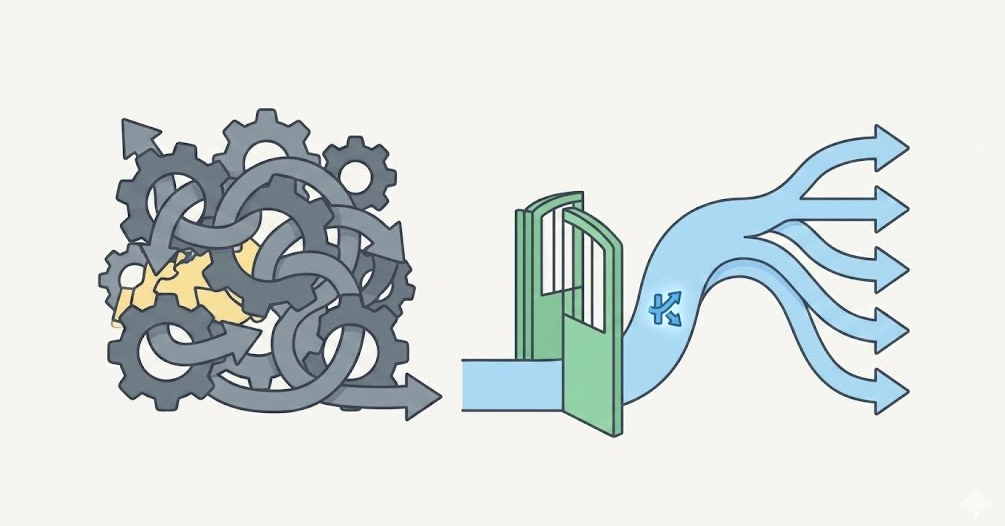

When managing computational tasks, there are three fundamental approaches to consider: sequential processing, parallelism, and concurrency, each handling tasks in a different way as illustrated in the image above.

Sequential processing will process tasks one by one, only picking up the next task once the current one is finished.

Parallelism involves multiple workers executing tasks simultaneously, using for example multiple CPU cores with each processing different data.

Concurrency on the other hand is about efficiently managing multiple tasks that may not run simultaneously. One worker juggles several tasks by switching between them when one is waiting.

For I/O-heavy applications, concurrency can often deliver better performance with reduced resource usage when compared to adding more parallel workers. In a scenario that doesn’t support concurrency, an increase in workers won’t be helpful since the threads will still be blocked waiting on the responses. When concurrency is supported a single worker can make progress on one task while another waits for a response, using the underlying resources more efficiently.

Concurrency therefore will enable the system to maximise worker utilisation, and make effective use of parallelism.

This distinction becomes crucial when designing systems that spend most of their time waiting for external services.

Coroutines: Concurrency Done Right in Kotlin

Kotlin coroutines introduce lightweight, cooperative multitasking, allowing thousands of concurrent tasks to run on just a handful of threads.

Unlike traditional threads which block and remain idle during I/O operations, coroutines suspend, allowing a single thread to efficiently juggle multiple tasks.

When a coroutine encounters a `suspend` function, for example a non-blocking database call or network request, it yields control to its dispatcher. This suspends the coroutine without blocking the thread. The dispatcher can then use the same thread to immediately run another coroutine. This cooperative approach enables applications to handle massive concurrency with minimal resource overhead.

Dispatchers

A coroutine dispatcher is responsible for determining what threads a coroutine uses for its execution. Depending on the use case, different types can be used:

- Dispatchers.Default is optimised for CPU-intensive tasks and is the dispatcher usually used by default when one is not specified in standard coroutine builders like `launch` and `async`.

- Dispatchers.Main ensures coroutines run only on the main thread and is usually used for UI-related tasks.

- Dispatchers.IO is specifically designed for offloading blocking I/O tasks to its dynamically expanding thread pool and is best used on applications with heavy use of blocking I/O.

- Dispatchers.Unconfined doesn’t confine its coroutines to any specific thread, leaving it to run unconfined in the thread that triggered the coroutine.

Scaling with Concurrency, Not Just Threads

This brings us to the central coroutine philosophy: they are plentiful and cheap.

Creating many coroutines is encouraged, as each can represent a single logical operation. Coroutines can be a better model for both concurrency and parallelism as they allow us to replace the “one task one thread” model with the “many tasks few threads” model while maintaining efficient resource utilisation.

When an operation waits for I/O, its coroutine suspends, freeing the thread to do other work. This avoids a bottleneck of thread-based systems: thousands of idle threads consuming memory. The result is dramatically improved performance and scalability for I/O-heavy applications.

Applying Coroutines to Real-World Performance Problems

Imagine a service integrated within a microservice architecture. This service processes tasks, which consists mostly of calls to other microservices in the system. This means most of the processing is network I/O, meaning threads spend time waiting, not using the CPU.

Let’s focus on possible traps engineers can fall into when designing a system like this, and how proper concurrent processing can help.

The Problem: Fighting the Framework

One of the possible traps we can fall into is forcing coroutines to behave like blocking threads. The example below defines a fixed number of tasks to be processed by a coroutine (`tasksToProcess`) and handles them sequentially. This approach misses the point of coroutines by running blocking operations without the ability to suspend their execution. Coroutines excel at handling many operations concurrently, by suspending and freeing resources when suitable.

The most critical issue is wrapping work in a runBlocking block, turning lightweight coroutines back into blocking operations:

(1..tasksToProcess).forEach {

runBlocking { processTask() } // Blocks the thread!

}This anti-pattern blocks a thread for the entire task duration, including all network I/O wait. From the runBlocking documentation:

This problem can be further worsened if the service artificially constrains the I/O dispatcher's natural capabilities:

// Artificially limiting what should be unlimited

private val ioDispatcher = Dispatchers.IO.limitedParallelism(maxParallelism)

Dispatchers.IO is specifically designed to handle blocking I/O by dynamically expanding its thread pool when threads become blocked.

By imposing limited parallelism, we're telling the dispatcher "never use more than x threads simultaneously" regardless of how many threads it could efficiently manage.

This is particularly wasteful in our scenario, which is heavily I/O bound with calls to external services.

It’s also useful to analyze how these tasks can be picked up by the coroutines handling them.

In a case where the service processes the tasks in fixed batches triggered by a scheduler, we will run into an optimisation problem:

- Set it too low, and the system finishes its batch early and stays idle, wasting time.

- Set it too high, and we risk overlapping batches which will lead to too many blocking operations simultaneously, overwhelming our limited thread pool and causing resource contention.

Furthermore, inside each batch, some coroutines will finish quickly and sit idle, while others are still working. This means that the total processing time is limited by the slowest batch, not the average.

In all the above scenarios we can see coroutines being treated as expensive resources to be rationed, but they are designed to be abundant and lightweight. They are wrongly optimizing for parallelism (having multiple workers) while ignoring concurrency (efficiently handling I/O waits).

The Solution: Embracing True Concurrency

The fundamental shift needed is moving from "how many workers can I create?" to "how many concurrent operations can I handle efficiently?"

Work Distribution

Channel-based work distribution can replace pre-assigned batches with dynamic worker pools where coroutines pull tasks as they become available:

val taskChannel = Channel<Task>()

// launch workers that will consume from channel

val workers = List(maxParallelism) {

launch {

for (task in taskChannel) {

processTask(task)

}

}

}

// insert tasks in channel

tasks.forEach { task ->

taskChannel.send(task)

}

taskChannel.close()This pattern eliminates load-balancing problems. We move from a fixed-size batch - which might be too large or too small - to a continuous stream of tasks. This way workers can consume tasks and stay busy until all work is done.

Thread Management

The above separation of concerns allows us to remove the artificial dispatcher constraints and let Dispatchers.IO handle blocking I/O efficiently while we control the parallelism by the number of workers:

// Let the dispatcher manage resources naturally

private val ioDispatcher = Dispatchers.IO // No artificial limits

// Control parallelism at the application level

val workers = List(maxParallelism) { /* worker coroutines */ }

- The number of workers controls and limits concurrency, ensuring that we don’t overwhelm external services with too many requests.

- The dispatcher optimizes thread management, spawning additional threads when necessary.

Blocking Anti-Patterns

Additionally, to eliminate blocking anti-patterns we can also replace runBlocking with proper suspend functions:

// Before: Thread-blocking

runBlocking { processTask() }

// After: Properly suspending

fun process(task: Task) { /* do some work */ }

suspend fun processTask(task: Task) = withContext(Dispatchers.IO) {

process(task)

}

This change allows coroutines to yield control during I/O operations instead of blocking threads. This approach ensures the system is efficient, and works with Kotlin coroutines instead of against them.

The Results and Future Opportunities

These changes can transform a service from a rigid parallel system to a truly concurrent one, delivering:

- Dynamic load balancing: Work distributes naturally based on processing speed.

- Proper parallelism control: Business logic concurrency managed by worker count, not dispatcher limits.

- Optimal resource utilisation: Threads stay busy handling ready-to-run coroutines.

- Natural backpressure: System automatically adjusts to capacity constraints.

For additional gains, non-blocking I/O can unlock even higher worker counts without thread exhaustion.

Pipeline architecture can also be restructured into specialized stages connected by channels, allowing independent optimisation and simultaneous stage execution.